Updated:

Updated: Transformation

Transforming organizations can feel like chasing windmills. You seem either too far removed from the real action or lack the flexibility to bring about lasting change–not an easy balance. Luckily, as architects we’re used to making trade-offs and routinely employ models to reason about those (often these models are expressed as sketches. So, why not utilize our analytical and visualization skills to depict engagement models? I actually did this in one of my career discussions and it helped me a great deal.

Freedom vs. Authenticity

While spending 5 years as a change agent in a very large organization, I routinely joked that I was really the chief organizational architect, merely disguised as the chief IT architect. My team introduced many amazing changes into the organization, such as a DevOps style of development, cloud platforms, automated deployments, infrastructure automation, pre-packaged monitoring components, and much more. As rewarding as the role was, it was also exhausting. Many things that our team was looking to implement were hampered by existing rules and processes. Naturally, our objective was to streamline those very processes, but if you set out to transform every process that you touch, from compensation and hiring to hardware provisioning and local software installs, you end up trying to boil the proverbial ocean–or chasing windmills. You’ll therefore have to pick your battles or at least postpone some.

Transforming an organization from the outside as a consultant or advisor makes you immune to a significant portion of those existing processes. For example, you don’t need to worry about promotions, labor contracts, overtime payments, perks, and likely get away with using non-standard (meaning, actually productive) workplace hardware (to be fair, we were able to get MacBooks for the team, albeit wrapped in a good amount of red tape). But on the flip side, the extra freedom also also isolates you from the reality of the organization–you might find ourself being very productive on your non-standard hardware while your full-time colleagues aren’t allowed to install PuTTY. Or you might preach grandiose improvement schemes involving agile self-governing tribes that might never take hold in the organization due to conflicting incentive systems and labor contract restrictions.

Any senior IT leader has had many folks tell them that they “just” need to transform their IT from a cost center to an innovation engine. Don’t be one of them! Instead, help make this change happen.

So, is there a “happy medium” on this spectrum, and what does the range look like in the first place? Let’s use our architect skills to find out.

Decision Model

Architects like models, so when I was meeting with my manager to discuss my career progression, I prepared a visual model. Following my preference for sketches, I kept the visuals very simple:

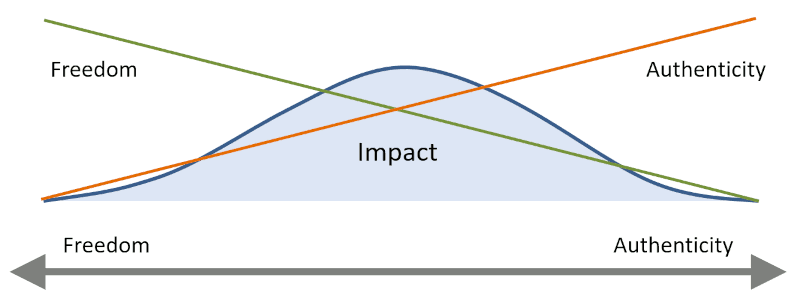

The graph depicts my mental model that to make an impact on an organization you need both authenticity and freedom. Without the former you won’t know the real problems and without the latter you won’t be able to fix them. My assumption was that any role that affords you more freedom, by being an external, would make you lose authenticity. Vice versa, being a regular full-time employee affords you full authenticity but at the expense of any freedom to make a change.

If you consider transformation impact the product of both authenticity and freedom, both end points result in zero impact.

I felt that my role at the time placed too far right on this model, not leaving me with sufficient freedom. So, i was looking to discuss ways to retain my authenticity in the organization but remove some existing constraints. Guiding a conversation with a mental model as opposed to a specific demand allows you to agree on model as a first step, even though you might not yet agree exactly where on the spectrum the answer lies.

Filling in the Spectrum

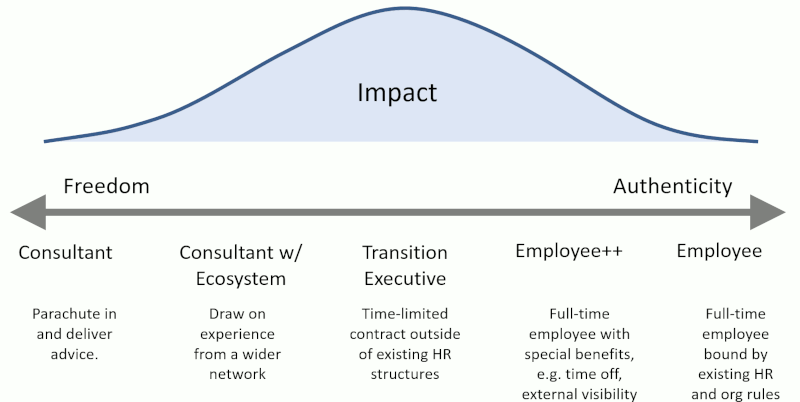

My former manager grasped the model immediate and correctly anticipated where the discussion was going: I was looking to shift left. The key question was how far. We know what the far left looks like – I have spent many years in professional services, creating awesome slide decks and strategy documents. What’s interesting is what lies in between:

I was leaning towards a Transition Executive role, meaning someone who’s fully embedded into the organization but isn’t subject to regular HR constraints. This way, I wouldn’t have to worry about raises, promotions, and perhaps expense policies (these are a common sore spot, not because I am looking to travel in first class, but because I had whole expense reports rejected because I consumed a $1 wafer from the hotel minibar after a 13h flight).

Slightly further to the left is the life of an independent consultant, but embedded in a supporting ecosystem of like-minded independents who routinely work for the same clients (it’s always been important to me to have people around me who I can learn from).

Naturally, my manager was more eager to explore what Employee++ could look like. Working off the same underlying model greatly aided this discussion.

Shifting the Curve?

I describe the ability to see more dimensions as a key trait of successful architects.

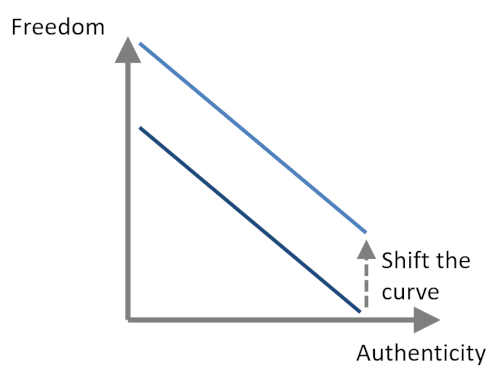

Whenever we see a linear trade-off between two ideals, we should explore whether we can turn the into two independent dimensions.

Naturally, plotting on two dimensions doesn’t instantly make the constrains disappear–they will still be forcing a trade-off. However, we can now have a richer discussion and consider whether we can shift the curve or change its shape.

I consider authenticity non-negotiable during a transformation. If you’re too far detached from reality, the whole effort is bound to become a paper exercise and you’ll be joining the long list of people who keep drawing rosy target pictures without much consideration as to how the organization might actually get there. Therefore, in my mind the exercise should be to find more degrees of freedom without sacrificing authenticity. An unexpected way in which I achieved that was by reducing my work week to 3 days. The remaining 2 days gave me the freedom to write, teach, or run workshops, and thus validate my approaches based on other organizations’ experiences.

Although being away for 2 days didn’t make the processes ailments during the other 3 days disappear, it made them ever so much more palatable as I could be looking ahead to 4 friction-free days—I sometimes wish I had that same setup today.

The third dimension – time

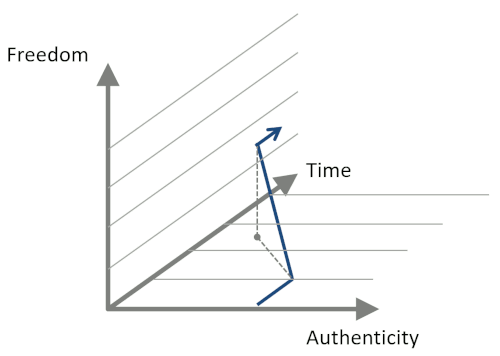

If you’re stuck in a trade-off, adding one more axis would be great. In reality, you can find such an axis: time. If at any point you’re stuck with loosing authenticity or freedom, perhaps there’s a reasonable progression over time? For example, you could embed yourself into the org to gain authenticity and build relationships, and then progress to steer change from the outside. In a way, my career discussion was an example of exactly that: after 5 years of authenticity, I felt I’d benefit from more freedom to keep making an impact without wearing myself out.

These curves aren’t as easy to draw on a two-dimensional screen, but the picture shows an example curve that stays on high authenticity, low freedom for a bit before shifting to higher freedom.

Can you plot your role as a change agent on a graph? It’d surely be interesting to see it – feel free to share via the social media links below.

Make More Impact as an Architect

The Software Architect Elevator helps architects and IT professionals to take their role to the next level. By sharing the real-life journey of a chief architect, it shows how to influence organizations at the intersection of business and technology. Buy it on Amazon US, Amazon UK, Amazon Europe